Dear reader,

I have been thinking about longing a lot lately.

It comes from the Old English langian, meaning “to yearn after,” rooted in lang, meaning “long.” And that’s what longing does! It stretches. Across time, across silence, across distances.

Longing is not the same as desire. Desire is active—it reaches, chases, pursues. Longing is quieter. It sits. Waits. Lingers.

If you’ve received my book, you’ve probably read the introduction and already know who Khan Baba is, and how much he means to me, and to my becoming.

But if you don’t know, let me take you with me. Let me tell you his story of longing.

From the 1980s to the early 2000s, in the Pinjore Gardens near Chandigarh, there lived a man called Khan Baba.

His real name was Kewal Krishan Sharma, but in a street play, he once played a character called Khooni Khan, and came to be known as Khan Baba thereafter.

Some saw him as a faqeer, some as a madman, some as poet-saint. For my mother and us, he was simply Khan Baba. A man we would often go and meet like one visits their relatives.

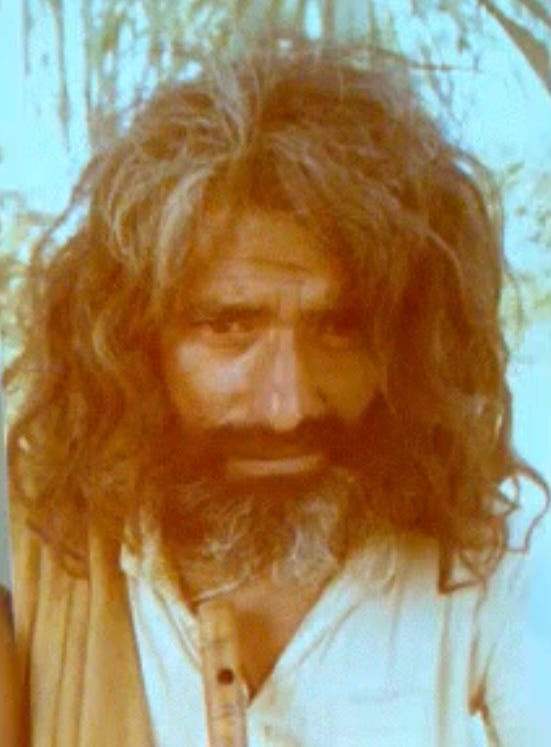

He would sit in the gardens, playing his flute, reciting poetry, and smoking far too many cigarettes. His clothes were ragged, his hair wild, and his eyes — deep and knowing.

He was fond of my mother. He called her beti. In 1989, before my mother’s complicated open heart surgery, he said to her: teri balayein maine apne sar le li, ja tujhe kuch nahi hota meri beti! My mother survived the surgery against all odds. Khan baba was so happy that he came to my mother’s wedding reception and sang for her. He would not normally leave the gardens or sing elsewhere.

There was something sacred between him and my mother. Something shared in silence. Unspoken but understood. Cancer stole them both from me. And I don’t know when or how but I became a keeper of their longing.

Today, I want to tell you the story of his longing in the only way I know how. With a poem I wrote for him:

Year 1999: I am a seven-year-old girl

With ancient eyes and curious hands.

I want to understand everything my fingers touch,

To know everything my gaze falls upon.

We’re out on a picnic at Pinjore Garden,

And there … my eyes fall on him.

To my seven-year-old self, he looks terrifying:

A shirt with a black lungi,

White untamed hair cascading

like waterfalls over his shoulders.

I just want to disappear

Under the hem of my mother’s firozi suit.

But before I can,

He looks at my sister, who must have been four,

And says:

“Kisi ki bazm mein guzre hue ae haseen lamhe,

Aa ke jee bhar ke tujhe pyaar karoon.”

That was the first sucker punch —

A memory-hole in my heart.

With my ancient eyes and curious hands, I learned:

Khan Baba had no home, no food to eat,

No family to call his own.

He never accepted alms,

But wrote poetry on crumpled papers,

Feeding on words as if his life depended on them.

Khan Baba smoked cigarettes — too many,

One after another, as if measuring time

Not by the hands of a clock,

But by the length of those burning sticks.

Now you do the maths: how many cigarettes

Did it take to wait for the love of his life

In the same garden, for over thirty years?

His lover never returned.

Perhaps he woke with ashes

In his mouth every morning. Or poetry.

Khan Baba carried so much sorrow and agony inside,

But never gave an ounce, a drop, of his sadness to anyone else.

Instead, he took in others’ sadness

And offered them temporary peace —

At the cost of his constant pain.

Khan Baba died alone.

In my dreams, he speaks still:

“Chala ja o raahi, chala ja o raahi…

Mujhe dekhne de khud apni tabahi…”

But I remain tethered to this spot,

Where a seven-year-old girl once learned

That love can be a lifelong vigil.

— A deathless hope.

For the longest time, I remembered Khan Baba only through my memory’s haze. But three or four years ago, Roshan Verma (on his YouTube channel Mission Haryana) posted a video that stopped my heart.

It was Khan Baba. His voice. His flute.

The video was shot in 1980 by a Polish woman named Radeshwari Singh, who had come to India for a soul searching journey. She would meet Khan Baba often and called him Divana Sahib of Pinjore Gardens.

Thanks to Roshan and Radeshwari, I can now show you his face. Let you hear his voice. Let you feel the echo of the ache that lived in him.

Three days ago, I went back to the same spot where Khan Baba would sit and sing. I carried my book with me. I sat exactly where I used to see him as a child.

I read this poem into the stillness he once filled with bansuri. And then I left a copy behind of my book behind. Not just for him, but for anyone who might need to find it. It felt like an offering.

Both my mother and Khan Baba are no longer in this world. But they were my first mirrors of sorrow, of strength, of poetry that rises from longing.

It felt only right to return it to where it all began. To gift my poems back to the garden that held us. To the ghosts who continue to raise me. To the longing I have come to inherit.

It’s the only way I know to say:

I remember.

I carry you.

So long,

Amy